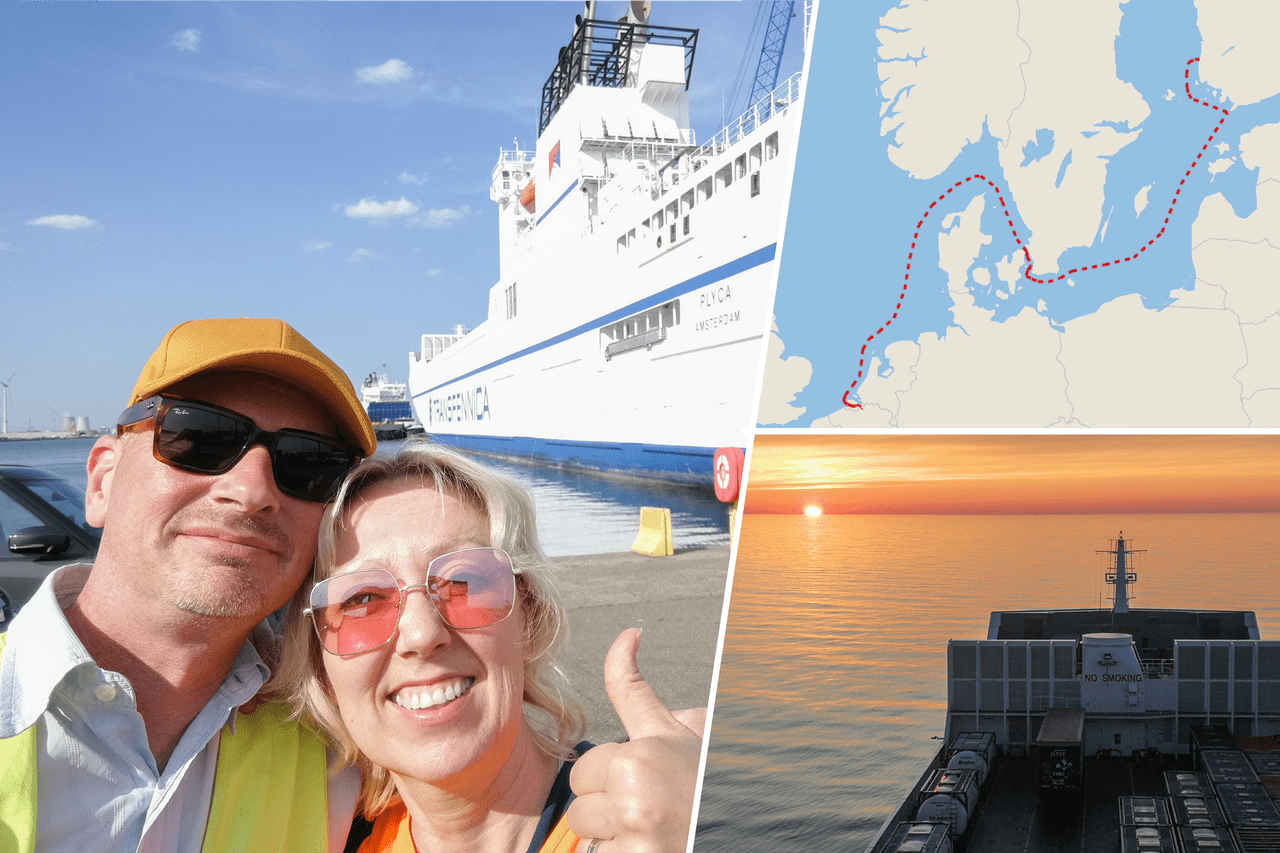

Eight days of travel on cargo ship Plyca, from Antwerp to Finland and back: "Nothing must and little can"

Eight days on a cargo ship across the Baltic Sea toward Finland and back. For some it sounds like a unique experience, for others it looks like eight days of confinement with boredom as their biggest fear. I belonged to the latter group. So it was a big surprise to me that on day seven I began to look forward to a longer freighter voyage. Or how the journey can be more important than the destination.

© Sacha Van Wiele

Where did you get the idea to volunteer to board a cargo ship for an eight-day trip? It was an oft-heard question when I explained my vacation plans. The reason was my wife Els. For years she had been walking around with this travel plan. She had an inexplicable curiosity for me about sailing on a freighter. For a long time I was able to hold off this boat until we ran into Joris Van Bree of CptnZeppos. He organizes trips on cargo ships. From then on we ran into each other frequently. Each time he inquired whether we had already made a decision. Joris suggested the Antwerp-Finland trip. "Good for beginners," he said. I no longer had a leg to stand on. We would spend eight days in July on afreighter.

On Friday evening, July 7, I am standing with my wife at Quay 1213 in the Port of Antwerp. There lies the Plyca of shipping company Transfennica. The freighter is 205 meters long and 26 meters wide. The crew numbers 19 heads. The majority are Filipino. The captain and two of his helmsmen are Dutch. We are eight passengers and one 17-year-old trainee who already wanted a taste of life at sea. He starts next school year at the college of shipping in the Netherlands. The loading of the ship was still in full swing.

I was uneasy about it. Eight days stuck on a ship with the only view being water, water and water, and a non-stable Internet connection. Doing chores with the crew is out of the question for safety reasons. The recreational offerings on board: a gym and DVD player in the passenger lounge. To combat boredom, I stuck my e-reader full of thick books.

Many people tried to convince me leading up to the trip that I was in for an incredible experience. "Sacha, you should definitely be on the bridge when you go through the locks and then sail down the Westerschelde. Really the best moment of the trip," says ship spotter Paul.Only the pilot in Antwerp decides otherwise. The Plyca would normally set sail at 9:30 p.m., but no pilot was available. "We don't leave until 1:30 tonight," says Gerard Hollander, our captain for the next eight days.

In the dark we leave the port of Antwerp.

When we wake up in the morning, we have long passed Vlissingen. The captain has some catching up to do on day one. Therefore, we do not sail through the Kiel Canal between Germany and Denmark. This channel should have been a highlight, according to some. "That canal is way too unreliable," he says. "You normally take 14 hours, but it can be 24 hours." That sounds like the shipping version of the Antwerp Ring Road.

That first night is nothing like I naively expected. No gentle, sleep-inducing roar of the engines and lapping water against the bow. The engines roar through the ship. The two shafts of the propellers spin at full speed. We are cruising at top speed of 21 knots. That means consuming 4,300 liters of fuel per hour. Moreover, the cabin is above the air conditioning technical room.

The Plyca is a mighty machine. "We are the Ferrari among cargo ships," says the captain. It was built to make its way through the pack ice in the Baltic Sea, although it has been years since the captain saw any ice there. It's not quiet on the deck above the bridge, either. There you can hear the turning of the radars.During the one-time visit to the engine room, I am able to pick up some earplugs. They offer me a good night's sleep for the next few nights.

Space for movement is limited to the cabin, the bridge, the gym, the deck above the bridge and the stairs therebetween.

The rest, other than one guided tour, is off-limits to us for security reasons. "Our lives will be limited to this for the next few days," I say cynically to my wife. However, it is the last time she will hear me rave about this trip.

I wake up at 3 a.m. during the second night and decide to go to the bridge around 4. We are sailing to the east and thus the ideal time to see the sun rise. On the bridge, I meet Ensign Ivo. Red glow announces the dawn. I climb to the deck above the bridge. The Plyca is drawing ripples in the calm sea. A bright red pimple appears on the horizon. In the middle of the sea, I witness the dawn of a new day. I have the feeling of being the only witness to this spectacle, other than, of course, Ensign Ivo on the bridge. This trip cannot fail for this urbanite.

Literally starstruck, I ask Ivo if he can also enjoy such a sunrise. "It's beautiful," he says dryly. But the sea has something else in store for us. An hour after sunrise, the helmsman brings out the binoculars and points to the left of the ship. Two heads of probably pilot whales, a dolphin species, break the flat surface of the water. We see them emerge once more beside the ship. "We really don't see that much," Ensign Ivo says a little more enthusiastically already.

I stick to the bridge and get a crash course on radar and maritime navigation rules. A brown layer is sticking on the horizon. "That's what we're all pumping into the air," says the helmsman.

On a cargo ship bridge, there is a captain, a helmsman at the helm and a navigator. I see that in the movies anyway. In reality, a freighter is steered by computer or autopilot. The captain and the three helmsmen relieve each other on the bridge every four hours. So there is usually only one man on the bridge to see if the computer is doing what it is supposed to do and if it is necessary to deviate from the charted route. Only at night is a sailor along on the bridge to keep an eye on things.

Keeping an eye on the sea is really necessary.

For example, sailors are not highly regarded by the crews of cargo ships. They even have an international nickname: WAFIs or Wind Assisted Fucking Idiots. Not only sailors are always aware of the risks at sea. On the narrow straits between the Danish capital Copenhagen and the Swedish city of Malmö, the captain sees a white dot. It looks like a breaking wave. It is too small to appear on the radar. It turns out to be a small motorboat in the channel for cargo ships, and it is also sailing against the direction. The captain sighs as we pass the meager little boat.

The rhythm of life on the ship is determined by the meals: breakfast at 7 am, lunch at noon and dinner at 5 pm. We don't eat together with the crew. Everyone regrets that, but we understand. Months the crew is on this ship, forming a community. Eating together is a free moment with each other. Having tourists join us could be seen as a violation of their free time.

Thanks to the nice weather, we spend a lot of time on the deck above the bridge. There we sit in the front row as we sail past the city of Gothenburg in Sweden. Queen Margrethe of Denmark was in her summer palace, as the Danish flag flies at this impressive palace. We pass the Öresund Bridge between Copenhagen and Malmö, made famous by the television series The Bridge. Already smiling, we smile at the cruise ships docked in Copenhagen. They are floating apartment blocks that hold up to 5,000 passengers. We don't miss the bingo afternoons, the performances, the swimming pools or an "all you can eat" buffet. We are more than satisfied with the offerings on Plyca.

In the Baltic Sea, world news is not far away. Written in pencil on the map of sea routes is research on the Nord Stream pipeline. This important pipeline was sabotaged in 2022. We sail past the place, but of course there is not much to see. "The war in Ukraine is also noticeable in the Baltic Sea," says the captain. "There are many warships sailing there."

Two days at sea are followed by three days when we can spend a few hours on land.

Because of the calm sea, we don't suffer from sea legs. The Plyca will unload and load in the Finnish ports of Hanko and Rauma. Hanko gets the prize of the most beautiful berth. From the porthole of our cabin we look out on a small bay with boathouses. Rauma's town center, with its wooden houses, has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There is plenty of time to visit them.

On the sailing route to Rauma is a group of islands. Sailing around it would take six hours, but sailing through it is two hours shorter. The captain opts for the short route. "So we get the scenic route," I say, laughing. Full of admiration, I watch the 205-meter cargo ship navigate between the islets. After Rauma, it's back toward Antwerp.

Besides reading and exercising in the Eastern Bloc-feeling gym, I write in the cabin in a journal. Only I look out the porthole at the shimmering sea and cargo ships more than at my ipad.On some stretches of our trip, we see only sea. A fellow passenger asks how far now is the nearest land. The captain looks at a screen: "at 45 meters". We look out with some surprise and then uncomprehendingly back at the captain. He points down with his finger: "45 meters below the ship."

For the crew, of course, a day looks different. You sometimes meet the sailors in the stairwell. You can see their presence by their slippers at the door of their staterooms. Occasionally orange spots move across the deck, the color of the sailors' everywhere. "On a ship, there is always work," the captain emphasizes. "Everything has to be constantly maintained. Machinery has to be lubricated. On this ship, there are a thousand lights. When the sea is choppy, they check that the cargo is still secure."

On the penultimate day, the ship is on schedule to enter Antwerp.

The captain captures a pilot. Then disaster strikes. A leak causes the engine room to fill with exhaust fumes. One propeller is shut down. The Plyca's speed drops from 21 to 13 knots. The ship veered to the right. Time is again in danger of being lost. If the Plyca does not reach Flushing in time, the pilot must be cancelled, and hours are again in danger of being lost. The captain remains calm, but I experience a small surge of adrenaline. After seven days of rest, that doesn't take much. After lunch a solution is found and the ship sails again at 21 knots.

The Plyca sails through the Kieldrecht Lock at 3 o'clock Saturday morning. After a final breakfast, we disembark at 8 a.m. on Saturday. Have I now experienced what life is like on a freighter? Not really. Filipino sailors spend up to 10 months on board. This is not easy mentally. We are privileged tourists who could rest, enjoy the sea and the landscapes. Nothing had to and little could. One thing does surprise me. It tastes like more. If my spouse were to suggest spending 12 days on a freighter, my enthusiasm would be impossible to dampen.

Cptn Zeppos as pilot for voyages with cargo ships

The Antwerp-Finland trip was booked with the travel agency Cptn Zeppos. It offers exclusively voyages with cargo ships. The inspirer is Joris Van Bree. He wants to introduce people to the world of shipping. Cptn Zeppos has a wide range of destinations, including Belfast, the Canary Islands, Morocco and Cuba. The longest voyage by freighter is from New York to Asia and back to New York. The passenger then spends 119 days at sea. A single trip to a destination is also possible. On some trips, the car, motorcycle or camper can be taken on board.

The eight-day Antwerp-Finland trip costs 1,108 euros per person for a double cabin. Those who travel on a freighter must meet some conditions. The passenger must not be younger than 6 and older than 82, have a valid passport and be able to present a recent medical certificate.

READY TO START YOUR ADVENTURE?

Welcomeaboard.

Your story starts with telling us on which sea or ocean you want to spend your time and when you want to start your adventure.

CONTACT US